More Than Just Hitting Record: A Beginner's Guide to Cinematic Storytelling

Ever wonder how your favorite films look so beautiful? It's all about cinematography. Let's dive into the basic principles that turn a simple video into a visual story.

Have you ever watched a movie and been completely captivated, not just by the actors or the plot, but by the sheer visual poetry of it all? That deliberate, almost magical quality of the light, the way a camera glides through a room, or how a simple close-up can convey a universe of emotion—that, my friends, is the art of cinematography. It’s a language all its own, spoken not with words, but with light, composition, and movement.

Honestly, when I first picked up a camera, I thought my job was just to point it at the interesting stuff and press record. I figured the expensive gear would do the heavy lifting. It was a humbling (and slightly expensive) lesson to learn that a camera is just a tool. The real magic comes from understanding how to use that tool to tell a story, to make an audience feel something specific. It’s about transforming a passive viewer into an active participant in the world you’re creating.

The person behind this magic is the Cinematographer, or Director of Photography (DP). They are the visual architects of a film, working closely with the director to translate the script's themes and emotions into a tangible, visual experience. Every choice, from the type of lens to the color of the light, is a brushstroke on a larger canvas. For anyone wanting to create more compelling videos—whether for a personal project, social media, or a future blockbuster—grasping these fundamentals is the first giant leap.

The Power of Light: Painting with Shadows and Glow

Before anything else, there is light. It’s the most fundamental element of visual storytelling. Light doesn't just illuminate a scene; it sculpts it. It directs the eye, creates mood, reveals texture, and can tell us how to feel about a character or a place before a single word is spoken. Learning to see and shape light is perhaps the most crucial skill a cinematographer can develop.

A classic technique that forms the bedrock of lighting is the Three-Point Lighting setup. It’s a wonderfully simple yet effective way to create depth and dimension. It consists of a Key Light, which is your main, brightest light source on the subject; a Fill Light, which is a softer light used to "fill in" the harsh shadows created by the key light; and a Back Light (or rim light), which hits the subject from behind to separate them from the background, creating a subtle outline. You don't need a Hollywood budget to try this; you can use lamps, windows, and reflectors to practice this principle.

But the rules are just a starting point. The real artistry comes from knowing when to break them. For instance, Low-Key Lighting uses high contrast and deep shadows, often with just a single dominant light source. Think of the dramatic, mysterious look of a film noir or a tense thriller. On the flip side, High-Key Lighting is bright, airy, and has very few shadows, creating a sense of optimism, cleanliness, or even heavenly glow, common in comedies and commercials. The choice between them is purely about emotion and story. What do you want your audience to feel in this moment?

Composition is King: Arranging Your World in the Frame

If light is the paint, composition is the canvas and the arrangement of the subjects. It’s how you organize the visual elements within your frame to create balance, guide the viewer's eye, and imbue the shot with meaning. A well-composed shot feels intentional and satisfying, while a poorly composed one can feel chaotic or boring.

The most famous principle here is the Rule of Thirds. Imagine your frame is divided by two horizontal and two vertical lines, creating a 3x3 grid. Instead of placing your subject smack in the center, try placing them along one of these lines or at one of the four intersection points. This simple shift often creates a more dynamic, balanced, and visually interesting image. It gives the subject "breathing room" and allows the viewer's eye to move more naturally through the frame.

But don't stop there. Look for Leading Lines in your environment—roads, fences, hallways, or even the direction of a person's gaze. These lines can act as arrows, subconsciously directing the viewer's attention toward your subject. Also, think about Depth. You can create a sense of a three-dimensional world by placing objects in the foreground, middle ground, and background. This layering makes the scene feel more immersive and less like a flat picture.

Another powerful tool is Headroom. This refers to the space between the top of your subject's head and the top of the frame. Too much headroom can make the subject feel small or insignificant, while too little (or cutting off their head) can feel cramped and uncomfortable. Finding the right balance is a subtle art that adds a layer of professionalism to your shots.

The Story in Movement: Your Camera's Dance

The way a camera moves—or doesn't move—is a core part of cinematic language. A static, locked-down shot can feel stable, objective, or even trapping. In contrast, camera movement can inject energy, reveal information, and mirror a character's emotional or physical journey. Every movement should have a purpose.

Simple movements can have a huge impact. A Pan (pivoting the camera horizontally) can follow a character or reveal the vastness of a landscape. A Tilt (pivoting vertically) can emphasize the height of a building or reveal something on the ground. These are the basic building blocks of camera motion.

More complex movements often require more equipment, but the principles are what matter. A Dolly shot, where the entire camera moves forward or backward (often on a wheeled platform), can create a sense of intimacy as you move closer to a character, or a sense of detachment as you move away. A Tracking Shot follows a subject as they move, keeping them in the frame and making the audience feel like they are right there with them. Even the raw, shaky energy of a Handheld shot can be used to create a sense of urgency, realism, or a character's frantic state of mind.

The key is motivation. Why is the camera moving? Is it to reveal a hidden clue? To follow a character's gaze? To build suspense as we creep around a corner? Moving the camera just for the sake of it can be distracting. But when movement is tied to the story, it becomes one of the most powerful tools in your arsenal.

Your Window to the World: Lenses and Focus

Finally, let's talk about the eye of the camera: the lens. Different lenses see the world in different ways, and your choice of lens dramatically affects the look and feel of your image. The focal length of a lens—measured in millimeters (mm)—determines the field of view and the magnification.

Wide-angle lenses (e.g., 16mm, 24mm) capture a very broad field of view. They can make spaces feel larger and are great for establishing shots of landscapes or cityscapes. They can also create a bit of distortion at the edges, which can be used for creative effect. Telephoto lenses (e.g., 85mm, 135mm), on the other hand, have a narrow field of view and compress the background, making distant objects appear closer. They are fantastic for portraits, as they isolate the subject beautifully from their environment. A "normal" lens (often around 50mm) provides a field of view that feels most similar to the human eye.

The lens also controls Depth of Field—how much of your image is in focus. A "shallow" depth of field, where your subject is sharp but the background is blurry, is a classic cinematic technique used to draw attention directly to your subject. This is achieved with a wide aperture (a low f-stop number, like f/1.8). A "deep" depth of field, where everything from the foreground to the background is in focus (achieved with a narrow aperture, like f/11), is often used to show a character within their environment.

Mastering these principles won't happen overnight. It's a journey of constant learning, observation, and practice. The best thing you can do is to start shooting. Analyze the films you love. Ask yourself why the cinematographer made certain choices. But most importantly, get out there and tell your own stories, one frame at a time.

You might also like

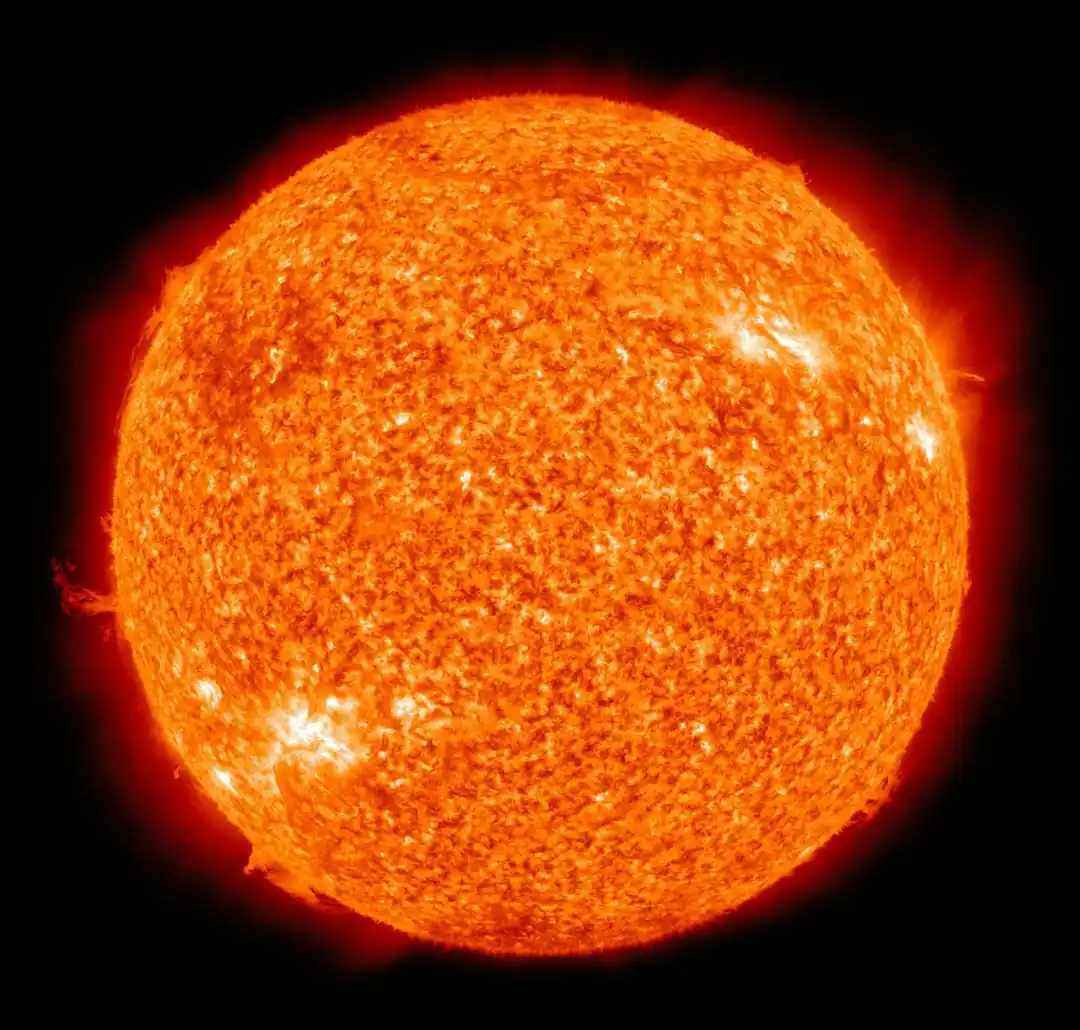

Forecasting Fire: How AI is Becoming Our Early Warning System for Space Weather

The sun's volatile nature poses a real threat to our tech-heavy world. Discover the groundbreaking AI tools that are learning to predict solar flares and protect our future.

Finding Your Zen in the Dental Chair: Can Mindfulness Tame Dental Anxiety?

Let's be honest, the dentist's office isn't exactly everyone's happy place. But what if a simple mental shift could transform that anxiety into calm? It's called mindfulness, and it might just be the key.

From Settlement to Security: A Guide to Investing Your Car Accident Money

Receiving a settlement after a car accident is a serious matter. It’s not a lottery win; it’s a resource to help you rebuild. Here’s how to approach it with care and make it last.

Your Older iPhone Isn't Obsolete: It's a Productivity Powerhouse

That slightly older iPhone in your hand isn't ready for the junk drawer. With the right lightweight apps, you can turn it into a fast, focused machine that outshines the newest models.

When to Walk Through History: The Best Time to Visit Philadelphia's Historic Sites

Thinking about a trip to the City of Brotherly Love? I've looked into the best seasons to explore its iconic landmarks, balancing weather, crowds, and atmosphere.